Plot Form: Want to Try a New One?

I love adapting to my writing craft ideas from artists other than novelists. For instance, I’ve learned a lot from painters. Recently I ran across the work of Paula Vogel, a Pulitzer-prize-winning playwright and her student Sarah Ruhl, also an accomplished playwright and a MacArthur recipient. Vogel identifies six plot forms and Ruhl adds a seventh plot form.

I am distinguishing plot form from story type.

Plot Form #1: Linear Aristotelian

According to Vogel, the Aristotelian cause-and-effect chain of action that heads toward catastrophe is “the crack cocaine of linear plot.”

The title image for this blog is from NASA of an asteroid hurtling close to earth in 2015. Fortunately it didn’t hit. However, Hollywood has had no difficulty imagining such a disaster scenario – man against the universe – and the epic drama it creates.

In Aristotle’s day the linear plot was men going to war. More recently it’s been men in business. Both the battlefield and the boardroom generate conflicts that produce winners and losers.

Needless to say, until recently, women were excluded from these two fields of combat.

Although the linear plot will always be with us, the point here is that there are other games in town.

Plot Form #2: Circular

This diagram is of a circular story type. It is not a diagram of a circular plot form.

A circular plot is not one where the main character ends in the place he or she started. Such a plot characterizes the Hero’s Journey. The diagram to the right is in the form of a circle. It is a circular story type.

A circular plot form is structural.

This plot form is structured like a round dance as a series of stories, with the hand of one person clasping the hand of a partner to create the first story. The partner, in turn, clasps the hand of the next person in line to create the second story. The stories continue until the first person’s hand is the last one clasped.

The classic example of this plot form is La Ronde by Arthur Schniztler written in 1897. Each of its ten characters appears in two consecutive scenes, with one character from the final scene having appeared in the first.

I see the circular plot form like this:

Think of each twist in her hair as composed of one plait from the twist before and one new plait, and this pattern continues until the last twist meets one of the plaits from the beginning.

Plot Form #3: Backward

The story begins with the end result of some series of actions, and the plot unfolds to reveal how the pieces came together to produce the result.

My perfect example would be The Hangover:

The story begins when three men wake up in a Las Vegas hotel room with no memory of the night before. The questions are: How did Ed Helms lose a tooth? Why does Zack Galifianakis have a baby? And where is the groom? Wait. There’s a tiger in the bathroom?

Great fun.

Plot Form #4: Repetitive

This is the polar opposite of the Aristotelean cause-and-effect chain of action that heads toward a dramatic conclusion. Vogel calls it tock-tick instead of the Aristotelian tick-tock of the bomb about to go off.

In Beckett’s Waiting for Godot not a darned thing happens. Didi and Gogo wait for Godot … who never arrives.

Sometimes that’s life.

Plot Form #5: Epic or Associative

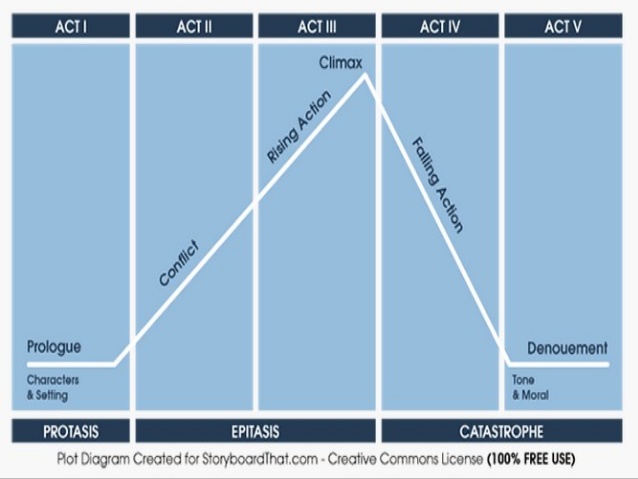

In short, all of Shakespeare who dramatized historical and political circumstances for his contemporary audience. We’re all familiar with his five-act plot structure:

Plot Form #6: Synthetic Fragment

When all time periods exist at once. For theater Vogel offers Angels in America. For novels I recommend Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife.

These are Vogel’s six. Ruhl adds:

Plot Form #7: Ovidian

In 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, Ruhl notes:

“In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he begins, ‘Let me begin to tell of forms changed.’ His emphasis … is on transformation, rather than a scene of conflict or rational cause and effect. Gods becomes swans, people become trees, people fall in love and die.”

The god Zeus becomes a swan to seduce Leda

Ovidian transformation opposes the clear moral in favor of the pleasure of one thing becoming another thing and then another.

“The play,” Ruhl writes, “takes pleasure in change itself, as opposed to pleasure in moral improvement.”

Ovid is the yin to Aristotle’s yang.

The Ovidian plot form reminds me most of the romance. Sure, there’s an element of moral since readers are rooting for “the better man” or “the better woman” to win. (And, of course, love is routinely compared to a battlefield.) Yet the real pleasure of the story comes in witnessing the transformation as the characters fall in love.

As a reminder, the Roman poet Ovid also wrote The Art of Love.

Are you stuck in the linear plot form? Time to try another!

For more tips on writing a novel, visit my complete guide on writing a book.

Categorised in: Writing, Writing Inspiration, Writing Tips

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment